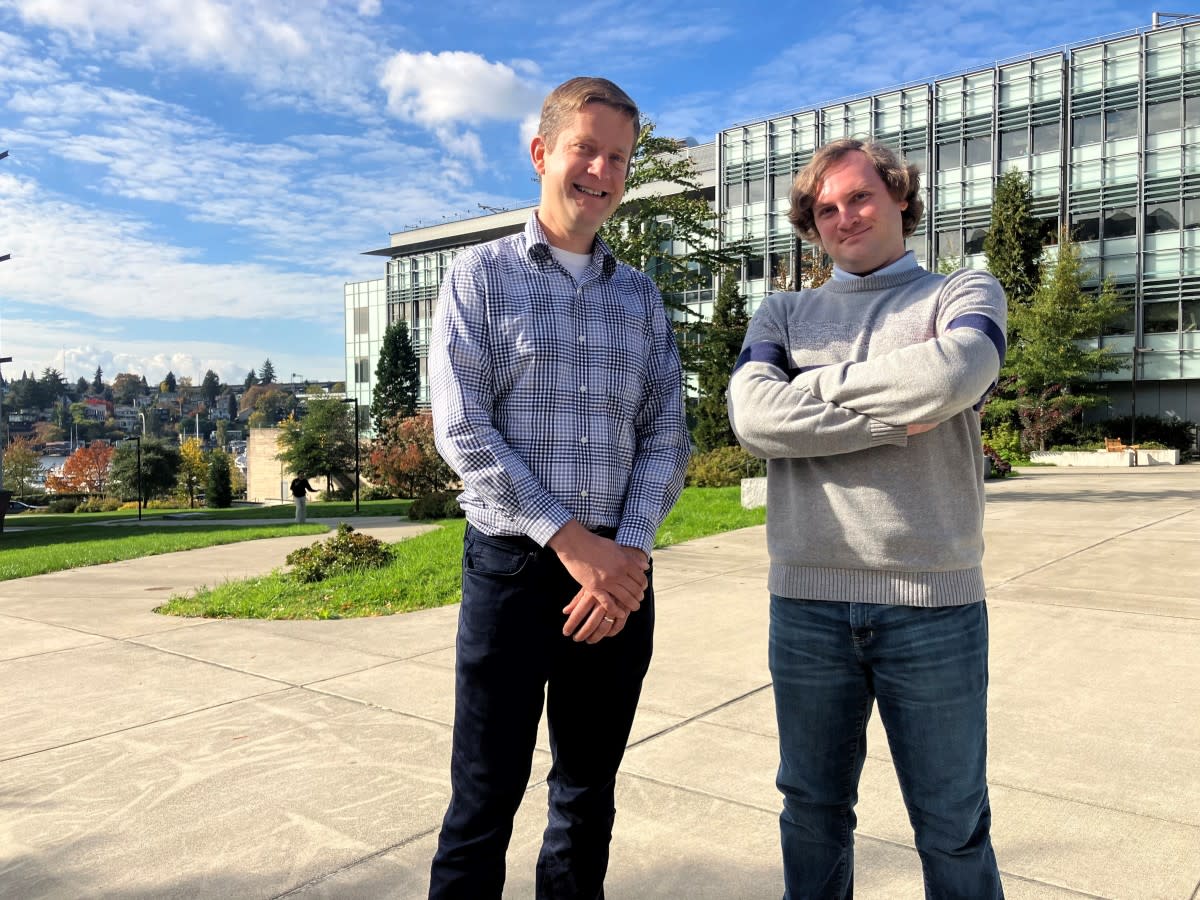

Ph.D. candidate Sam Smukowski (right) with his PI and thesis advisor Dr. Paul Valdmanis.

Ph.D. candidate Sam Smukowski (right) with his PI and thesis advisor Dr. Paul Valdmanis.

It’s likely that most graduate students in the UW Department of Genomic Sciences, especially those facing the expectation to complete their dissertations within six months, do not have books by Friedrich Nietzsche, Jean-Paul Sartre, and Franz Kafka on their nightstands. But then, Sam Smukowski is not like most people immersed in genomic sciences and medical genetics.

“Sam thrives under adverse conditions,” said Dr. Paul Valdmanis, who leads the lab in which Smukowski works and serves as advisor to his dissertation. “He is a mature and hardworking individual who adapts well to the ebbs and flows of a new lab.”

Flowing, but not ebbing, also characterizes the journey on which Smukowski has embarked toward a career researching molecular differences in neurodegenerative diseases. The catalyst for that journey occurred in third grade at his elementary school in Green Bay, Wisconsin. The school is named after Christa McAuliffe, the teacher who perished in the Space Shuttle Challenger disaster in 1986.

“Everything at the school is space-themed,” Smukowski said. “There are murals of planets and space shuttles in the auditorium. It is the core of the school. These were my early impressions of science.”

Isn’t space exploration a remote, if not distant, field of science from genetics?

“As far as science goes, they both are founded on an attitude of discovery,” he said. “I’m fascinated with unknown things. With space, you can draw a connection between this unknown realm for you to pioneer. The same goes for human biology.”

Fast-forward from third grade to Smukowski’s first year of undergraduate studies at the University of Wisconsin at Green Bay, where he took an introduction to genetics course. Coincidentally, CRISPR-Cas9, the technology enabling scientists to edit the genome by removing, adding, or altering sections of DNA sequence, was announced that same year.

“My professor at a time was absolutely excited to share the CRISPR discovery,” he said. “And I was thinking, ‘Wow, we now have all the tools to structure – and restructure – DNA, and potentially change the genetic makeup of living organisms.’ It was incredible. And from there, I knew this is where I wanted to focus my studies.”

After one year, he transferred to the Madison campus of the University of Wisconsin to acquire a bachelor’s of science in genetics. His extracurriculars included the school’s philosophy club, “Atheists, Humanists, & Agnostics at UW-Madison,” in which he served as the club’s programming chair.

I needed the time to build the skills in order to hit the ground running when starting a Ph.D.'

Following his degree, he sought to bolster his scientific skills by working as a research technician in the Neurology Department at Northwestern University in Chicago. Smukowski developed a specialization in mass spectrometry proteomics, which he used to assess protein changes in mouse models of neurodegenerative diseases, including Alzheimer’s Disease and fragile X syndrome. He also managed the lab’s mouse and rat colonies, totaling approximately 500 animals, as well as maintained laboratory equipment.

“The techniques I learned were foundational to my decision to pursue graduate school,” he said. “I needed the time to build the skills in order to hit the ground running when starting a Ph.D.”

Smukowski arrived at the UW Department of Genome Sciences in September of 2018 and joined Valdmanis’s lab because of the principal investigator’s background in gene therapy and the opportunity to learn RNA sequencing to complement his skills in proteomics. RNA sequencing has been fundamental in Smukowski’s dissertation work studying RNA synaptic mislocalization in Alzheimer’s Disease.

“Sam has made some profound insights into our understanding of the molecular contributions to Alzheimer’s Disease,” Valdmanis said. “He has identified key pathways that have gone awry through analysis of post-mortem brain samples. Moreover, he is working to devise methods to circumvent some of the pathological hallmarks of disease.”

So, what does Smukowski want to do after he defends his dissertation and is awarded a Ph.D.? Stay in academia to conduct research and teach? Pursue research in the private sector?

Like the crossroads where he stood after completing his undergraduate studies, he is open to any opportunity that comes his way. But, as he did when working at Northwestern, he is intentional about finding the answer.

“I’m exploring,” Smukowski said. “I’m attending conferences, networking with people in different sectors, and considering various directions.”

He may discover additional insights from a quote by Franz Kafka: “Paths are made by walking.”